From Start to Finish, a Brush With Greatness

Most of us cringe. That is, when we’re asked to sketch any semblance of a person or a face. Even in the simplest of board games, the challenge of drawing can cause sheer terror. Landscape designer Letora Anderson is not one of those people.

“I just did it because everyone in class was participating,” she said, laughing. “I think that was the first time I actually received recognition for something.”

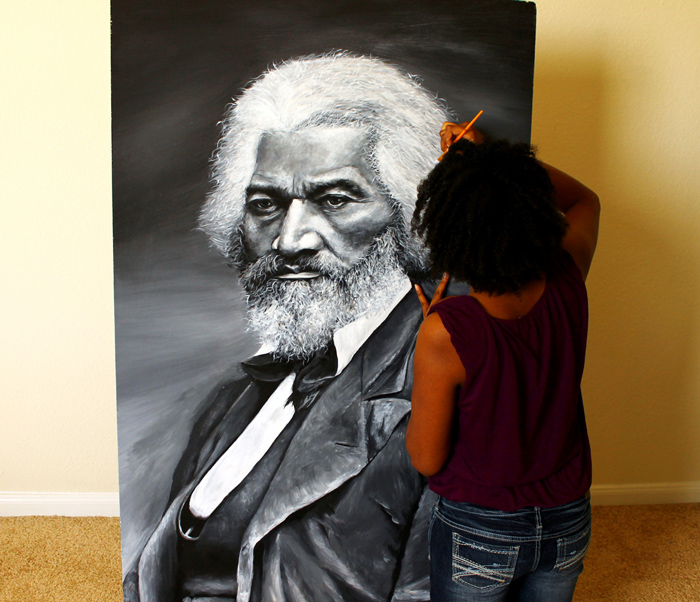

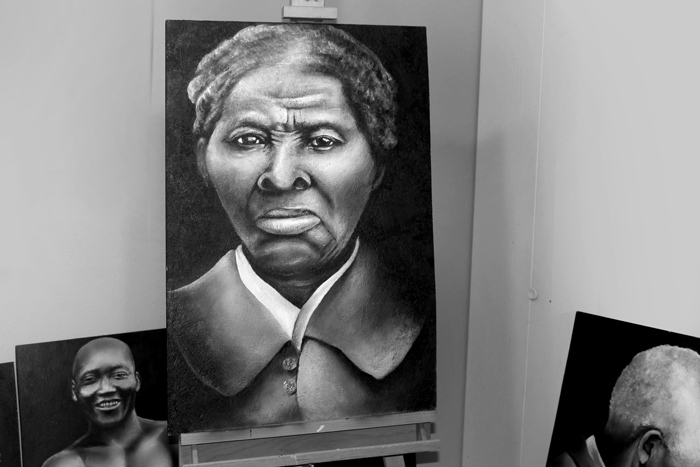

Today her art portfolio includes remarkably detailed portraits of historical figures such as abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, who were each born into slavery during the 1800s, plus paintings of baseball great Jackie Robinson and the Tuskegee Airmen, who were the first black military aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps.

Born a slave, Frederick Douglass escaped at age 20 and became a world-renowned anti-slavery activist.

A BUDDING PASSION

It wasn’t long after that third-grade art competition that Letora could look at something and draw it with great detail. She sketched cartoon characters, and once in middle school began designing T-shirts for basketball teams. Enrollment into a public art program gave her more opportunities to paint and draw, but she said she didn’t learn much about specific techniques.

“I kind of did my own thing,” she said.

In high school, Letora created murals for sports teams and designed the school’s yearbook cover one year.

Her artistic talents were even recognized during her basic training stint in 2003. She served in the Louisiana National Guard during her senior year of high school and went to basic training in Fort Jackson, South Carolina. One day while hanging around the laundromat and crafting an album cover design for fun, a friend saw what she was working on and told their drill sergeant. Soon Letora began fulfilling requests for things such as a series of wall paintings around the barracks.

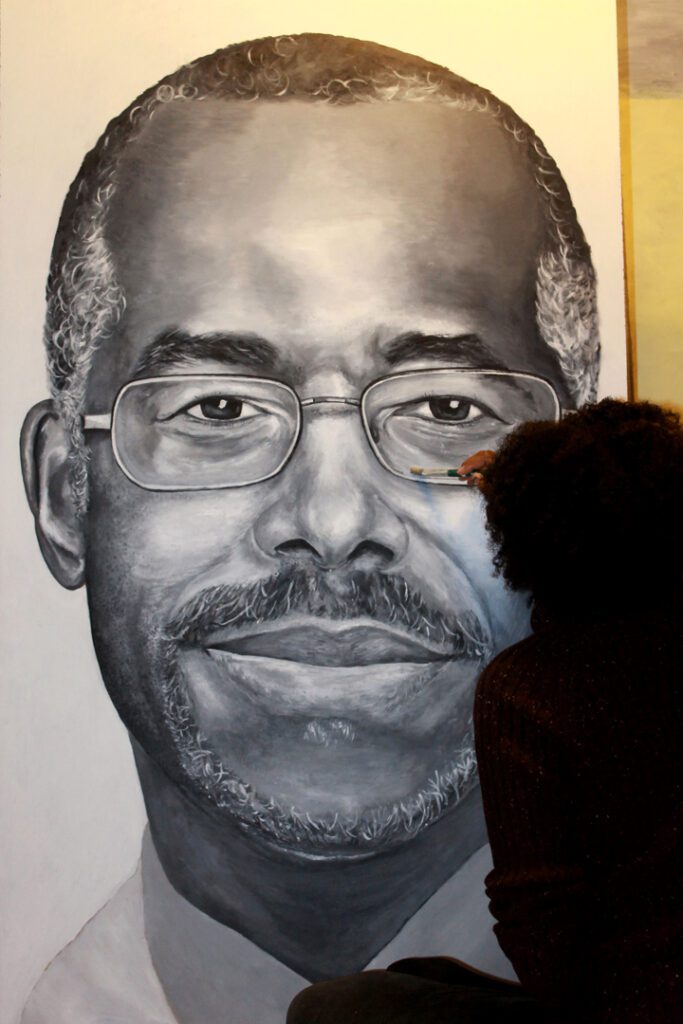

Letora’s process for painting a large portrait of Dr. Ben Carson, her first using oil paints, took approximately 14 hours. The wooden panels she uses are 5 feet by 3.5 feet.

“It helped because I didn’t have to do any of the chores everyone else had to do,” she said jokingly. “They would skip me in front of the chow line.”

Letora stopped painting when she went to LSU to pursue a bachelor’s degree in Landscape Architecture. Over the next several years, she met her future husband, got married, moved to Denver to work on her master’s degree and had two sons.

It wasn’t until she painted her boys in 2011 that she rekindled her passion for it.

SUBJECTS THAT INSPIRE

One rule of thumb Letora has is she generally wants to paint something or someone of interest to her. She has created illustrations and animations for churches. She enjoys illustrating children—and has given thought to illustrating children’s books. She has dabbled, naturally, in painting landscapes.

But one look at her website, letora.net, shows how motivated she is to paint figures who overcame. That’s where she clearly draws her inspiration.

“I have a thing in my wallet that says, ‘Stay the course.’ I think painting iconic figures helps me when—if I have a goal or tough situation—it helps me to stay the course. I think of their accomplishments and what they have overcome, and that I can definitely stay the course.”

The Tuskegee Airmen fought in World War II.

Painting the portraits, which she doubted she could do initially, is her passion.

“It’s kind of hard to get me to paint an idea or subject that someone wants me to paint if I’m not inspired by it,” she added. “I have to want to paint it.”

To get an idea of the timing, her portrait of U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson took about 14 hours from start to finish.

“They get faster each time,” she said.

Many of the large portraits she has painted were done on large, wooden panels (about 5 by 3.5 feet), which were formerly used as partitions or within walls of a cubicle. She started by applying a layer of gesso, which prepares or primes the wooden surface for painting. Without it, paint would more easily soak into the wood, or a canvas.

When she is painting a portrait, she said she usually starts with the eyes and nose, then works her way out to the edges. And she prefers to paint in black and white.

Harriet Tubman, who was born a slave, escaped to freedom in 1849 and became the most famous “conductor” of the Underground Railroad, helping to liberate hundreds of slaves.

“I paint black and white because, I guess I’m trying to get a level of detail in my paintings. I don’t want to focus on the color as much,” she said. “When I achieve the level of detail—and when I say ‘level,’ if I can achieve the hair looking the way I need it to look and the skin as far as texture—then I’ll go to color. But I haven’t.”

Most of Letora’s portraits have been painted using acrylic paints. However, she was influenced by a peer to try oils, so the Carson painting was her first. While oil paintings take longer to dry, they are considered more valuable.

Even so, Letora said she doesn’t really have an interest in selling her artwork. She has sold pieces on occasion—mostly requests completed for family or friends.

Painting is an outlet. Besides, she is her own worst critic.

“When I haven’t looked at them in a while, I drastically see what I would change,” she said.

If she only saw some of our stick-figure drawings.