Why Benchmarking Your Building’s Energy Efficiency Is So Important

Sustainability is a cornerstone of most buildings designed today. Sustainable design preserves critical resources such as energy and water, and incorporates materials that are environmentally friendly.

What can be done about older, existing buildings? After all, the last Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS) estimated there were 5.6 million commercial buildings in the United States, comprising 87 billion square feet.

They create a prime opportunity to reduce energy consumption and increase building efficiency across America.

Existing buildings may be renovated or retrofitted to improve their integrity and ensure they don’t leave negative environmental impacts. The first step for owners and facility managers to know how their existing buildings are performing in terms of energy efficiency is a process called benchmarking.

Three organizations—American National Standards Institute (ANSI), American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) and Illuminating Engineering Society (IES)—developed a methodology titled ASHRAE 100 to establish energy performance benchmarks.

The methodology provides a quick approach to assessing a building’s performance before conducting time-consuming and expensive building audits and energy studies. A building’s total energy usage can be reviewed, including electric, gas, steam, and chilled and hot water, to understand how the building is performing against similar types of buildings and to identify deficiencies.

It provides guidance on processes necessary to reduce the energy consumption of a building and really creates the foundation for an energy management plan.

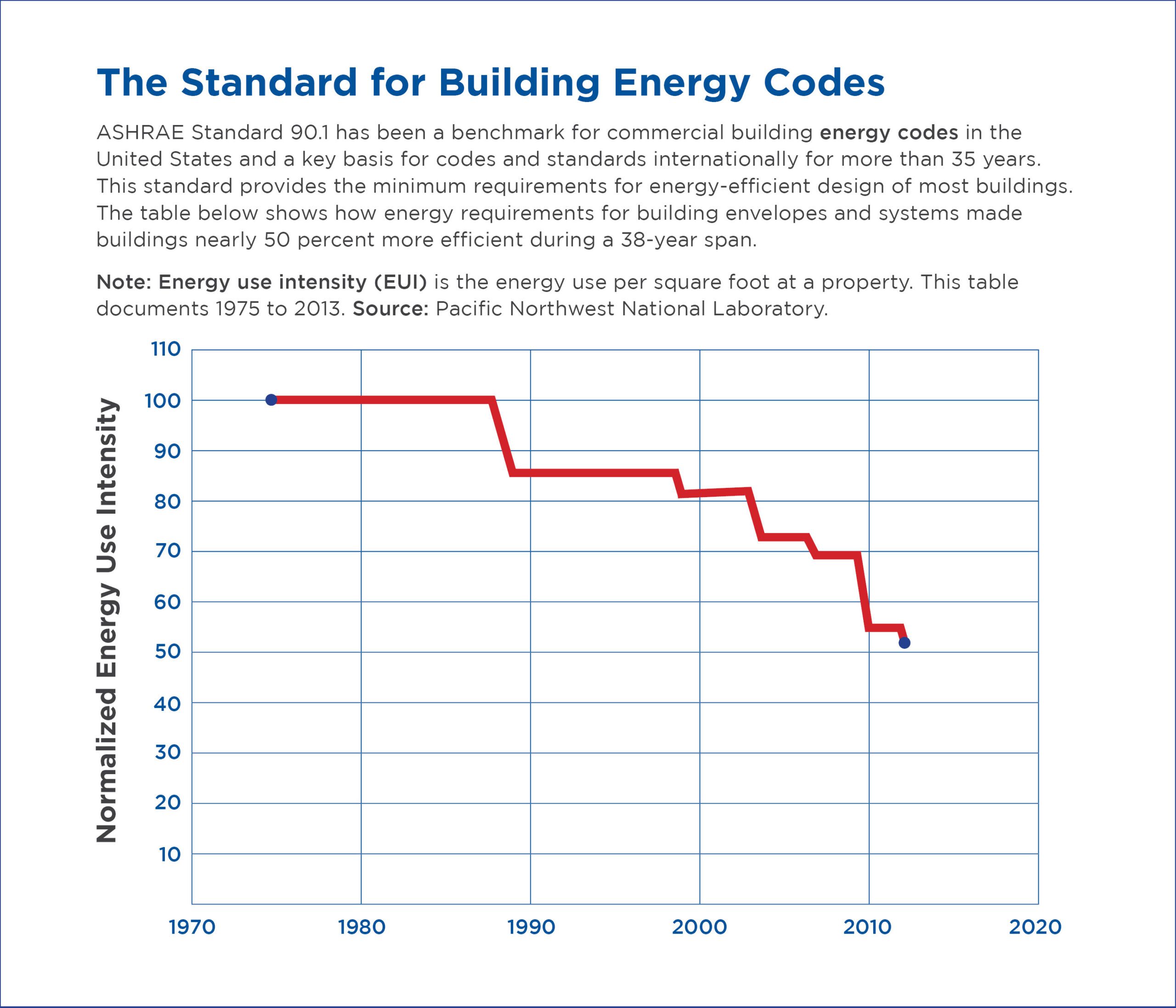

In the past, it was difficult to make comparisons with similar buildings because of several factors, including a building’s age, location and/or usage. Plus, building codes have changed significantly over the last 40 years. However, those codes have made a large impact on energy efficiency overall as evidenced in the following chart.

The Benchmarking Process

The first step in the benchmarking process—and ultimately to find opportunities for efficiency—is to perform an energy accounting of the annual building energy usage and convert it to a common energy metric such as a BTU. (A British thermal unit is the amount of energy needed to raise 1 pound of water 1 degree Fahrenheit).

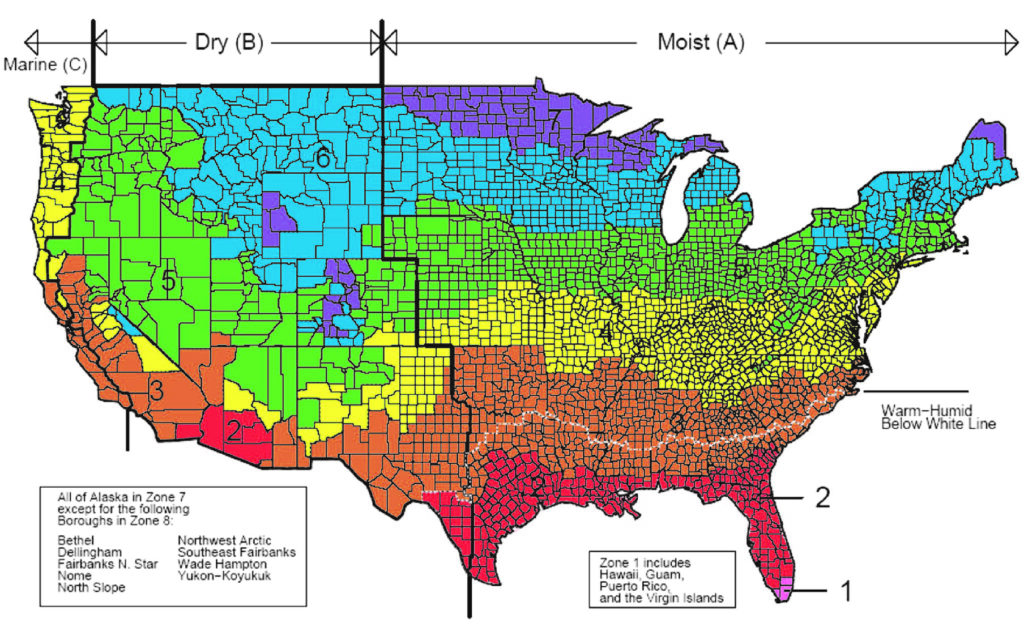

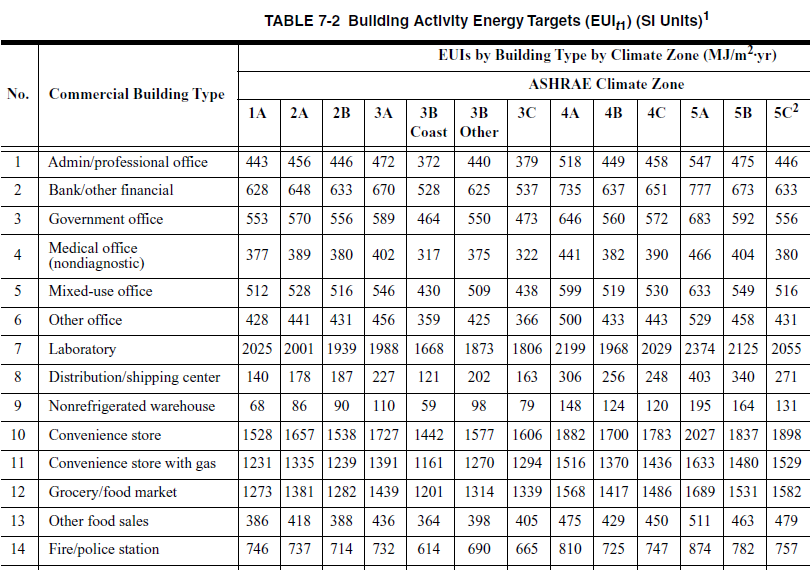

The energy use intensity (EUI) is found by dividing the total energy by the gross square footage. The EUI is then compared to other buildings of a similar type from a database. Factors are applied for actual building usage, such as number of hours and shifts, to normalize the data. The comparative database consists of thousands of buildings that the U.S. Energy Information Administration has compiled through CBECS. The recommended energy target would put the building performance in the top 25 percent for that type located in the same climate zone.

ASHRAE 100 methodology includes 53 building types—ranging from a refrigerated warehouse to a strip mall to a restaurant—for 17 climate zones in the United States. These facilities are educational, institutional, commercial and residential buildings. Industrial and agricultural buildings are not part of this methodology because of their unique processes. Other standards exist that are more specific to the function of those facilities.

The type of climate in which a commercial building exists factors into the building’s performance. (Courtesy/ASHRAE)

Energy targets are shown above for various types of buildings based on their climate zone location. These target numbers can be compared to those of similar buildings to assess where under-performing buildings exist. (Courtesy/ASHRAE)

From an Energy Target to a Management Plan

The need to conduct a more detailed energy management plan can be assessed once the energy target has been determined for each building. Managers can also develop a capital management plan to prioritize building improvements based on the buildings with the lowest performance.

The next step would require a qualified person such as an energy engineer to conduct a facility walkthrough to review the building envelope, domestic hot water, HVAC systems, refrigeration, lighting, controls and power distribution. A list of energy efficiency measures (EEM) is often prepared to prioritize capital improvements. A more detailed analysis with energy calculations and financial considerations may be required to justify project implementation.

In summary, this methodology, or a more refined approach, allows for study of the building’s energy-use efficiency in a quantitative manner. Understanding benchmarks such as these begins the process of making commercial buildings more efficient and using resources more wisely as we create energy master plans in conjunction with operations and maintenance.

For more information about the MEP Engineering team at Halff, write to Info-MEP@Halff.com.