Get PFAS Help Today!

Overview of PFAS

What are PFAS? Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large group (i.e., thousands) of man-made chemicals widely used in consumer and industry products due to their water, heat and oil-repellent properties. PFAS are considered the ‘forever chemical’ due to the chemical nature and structure. Regulatory limits are in parts per trillion which is equivalent to a single drop of water in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Facilities with potential PFAS contamination:

• Department of Defense (DoD) and Department of Energy (DOE) sites

• Fire training facilities

• Landfills

• Airports

• Water/wastewater plants

• Manufacturing facilities

• Semi-conductor sites

Potential sources of PFAS:

• Food packaging

• Grease-resistant paper

• Water-resistant fabrices (such as rain jackets, umbrellas and tents)

• Cleaning products

• Paints

• Personal care products (such as shampoo, dental floss, nail polish and eye makeup)

• Nonstick cookware (Teflon)

• Stain-resistant coatings (used on carpets, upholstery and other fabrics)

• Drinking water and food contaminated by releases from other sources

Learn more in our article: PFAS: The “Forever Chemical” Penetrating the World Around Us

PFAS Resources

National Regulations

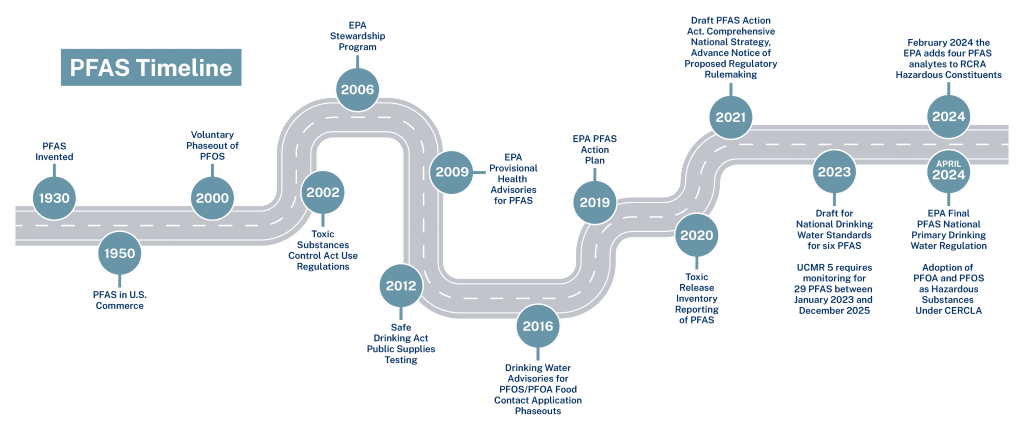

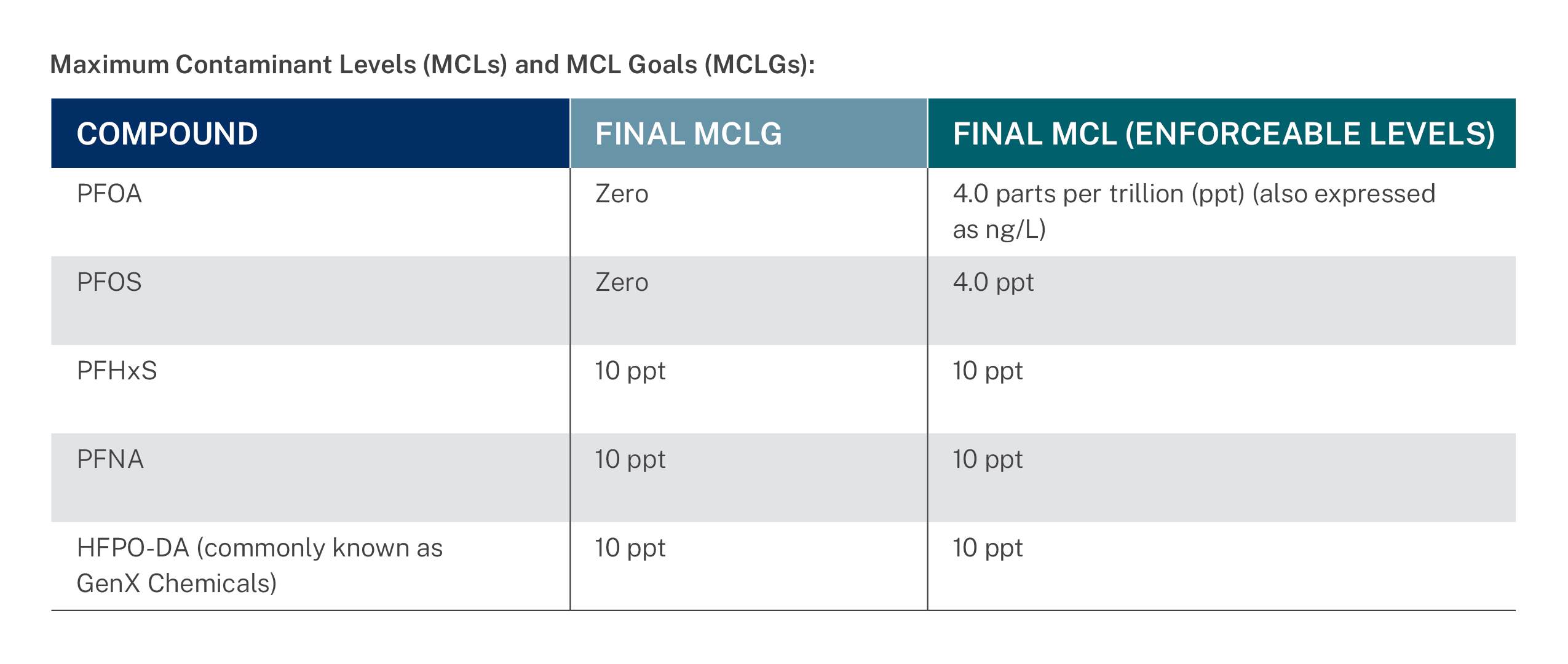

Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA): The EPA proposed national drinking water standards for six PFAS in March 2023 and finalized the National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) in April 2024. The EPA uses the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR) to collect data for contaminants that are suspected to be present in drinking water and do not have regulatory standards set under the SDWA. UCMR 5 requires monitoring for 29 PFAS between January 2023 and December 2025. With the recently promulgated rule, public water systems must monitor for and report these PFAS, and have three years to complete initial monitoring (by 2027), followed by ongoing compliance monitoring. In addition, public water systems have 5 years (until 2029) to implement solutions to reduce PFAS that exceed Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs).

Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA): The EPA published a final rule under TSCA that requires all manufacturers and importers of PFAS and PFAS-containing articles in any year since 2011 to report information to the EPA on PFAS uses, production volumes, disposal, exposures and hazards. This rule (40 CFR Part 705) was promulgated in January 2024 and any entity, including small entities, that have manufactured or imported PFAS in any year since 2011 will have 18 months to report PFAS data (24 months for small importers). Also in the past year, seven PFAS were added to the list of chemicals covered by the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) program, and the EPA finalized a rule that eliminated an exemption that allowed facilities to avoid reporting PFAS information to TRI when those chemicals are used in small (or de minimis) concentrations.

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA): EPA designated two of the most widely used per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) — perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), including their salts and structural isomers — as hazardous substances under the CERCLA, also known as Superfund. The rule requires entities to immediately report releases of PFOA and PFOS that meet or exceed the reportable quantity. Other provisions require federal entities that transfer or sell their property to notify about the storage, release or disposal of PFOA or PFOS on the property and include a covenant (commitment in the deed) warranting that it has cleaned up any resulting contamination or will do so in the future, if necessary, as required under CERCLA 120(h).

Section 306 of CERCLA requires the Department of Transportation to list and regulate these substances as hazardous materials under the Hazardous Materials Transportation Act.

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA): In February 2024, the EPA released two proposed regulations under RCRA that would add nine PFAS chemicals as RCRA Hazardous Constituents and clarify that the RCRA Corrective Action Program has the authority to require investigation and cleanup for hazardous waste, as defined under RCRA section 1004(5), which include emerging contaminants such as PFAS.

Clean Water Act (CWA): The EPA has taken several steps to use Clean Water Act permitting and regulatory authorities to restrict PFAS. In December 2022, the EPA released a guidance memo describing steps using NPDES permits that can be implemented under existing authorities, while the Office of Water works to revise Effluent Limitation Guidelines (ELGs) and develop water quality criteria to support technology-based and water quality-based effluent limits for PFAS. In January 2023, the EPA released its 15th Effluent Limitations Guidelines Plan (Plan 15). Plan 15 announced the EPA’s intent to initiate a POTW Influent Study of PFAS, which will focus on collecting nationwide data on industrial discharges of PFAS to POTWs, and also included the EPA’s intent to develop rules under the ELG’s program to limit PFAS discharges to waterways from PFAS manufacturers, metal finishing and electroplating, and landfills. As of February 2024, the new rules had not been published. No further action is anticipated under the Electrical and Electronic Components category; however, the EPA will continue to monitor PFAS discharge through the POTW Influent Study.

View information by state:

Arkansas | Florida | Louisiana | Oklahoma | Texas

The State of Arkansas does not have state required testing for PFAS compounds in drinking water. The state was waiting for the adoption of the EPA National Primary Drinking Water Regulations establishing maximum contaminant levels for 6 PFAS compounds.

Arkansas is home to four Federal facilities where AFFF was used. Previous investigations show concentrations greater than 1,000 part per trillion (ppt) of PFAS in groundwater around those facilities. In addition, Arkansas has seven facilities reporting detections of PFAS compounds in their drinking water but the detections are below the MCLs.

Interactive Map: PFAS Contamination Crisis: New Data Show 5,021 Sites in 50 States (ewg.org)

The Arkansas Department of Health (ADH) submitted comments on the previously proposed Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) National Primary Drinking Water Standards for six PFAS which include:

• Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)

• Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS)

• Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA)

• Hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFOP-DA)

• Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS)

• Perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS)

• (collectively, PFAS)

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) proposal was published on March 14th. (See previous blog post.) See Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-0W-2022-0114.

The Arkansas agency also incorporates the comments previously submitted by the Association of State Drinking Water Administrators.

ADH included the following in comments to the EPA:

• It is imperative that the proposed rule provide clear and achievable requirements for PFAS levels in drinking water without being overly burdensome on public water systems.

• Further evaluation should be conducted regarding the cost and potential adverse impacts on compliance with other existing drinking water requirements and water system viability (especially for water systems).

• 94.3% of the State of Arkansas’ 703 public water systems that are subject to SDWA jurisdiction serve fewer than 10,000 people (50% of those serve communities with fewer than 1,100 people).

• Small water systems use minimal or conventional treatment processes compared to conventional water treatment processes.

• PFAS treatment process will require proper disposal of waste streams that contain concentrated levels of these chemicals (and others).

• Treatment processes for PFAS are more complicated than existing drinking water treatment processes and will require additional training and certification of drinking water operators.

• Drinking water operators with advanced training certification are in short supply.

https://www.mitchellwilliamslaw.com/webfiles/ADH%20Comments.pdf

Please contact Halff for additional information of questions regarding PFAS regulations.

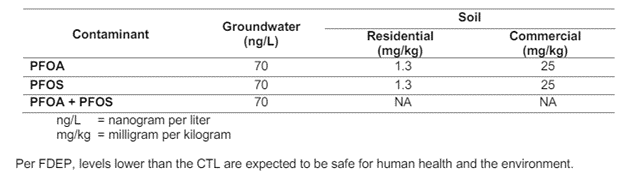

The State of Florida has state required testing for PFAS compounds in Drinking Water. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) is committed to the protection of the groundwater resources of the state and the public health and safety of their residents. The state established groundwater and soil cleanup levels in 2020.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) is the state’s lead agency for environmental management of Florida’s air, water, and land. As per Florida Administrative Code, Chapter 62-780, FDEP developed provisional cleanup target levels (CTLs) for PFOA and PFOS in groundwater and soil:

As part of these efforts, DEP’s Division of Waste Management routinely investigates sites where there is known or suspected soil and groundwater contamination statewide.

https://floridadep.gov/waste/waste-cleanup/content/dep%E2%80%99s-efforts-address-pfas-environment

Florida has 21 Federal facilities where AFFF was used, with an additional 12 PFAS fire training sites. Previous investigation shows concentrations greater than 1,000 ppt of PFAS in groundwater around those facilities. The state has 67 PFAS compounds in their drinking water but the detections are below MCLs or the compounds do not have MCLs.

Interactive Map: PFAS Contamination Crisis: New Data Show 5,021 Sites in 50 States (ewg.org)

The Florida Legislature is proactive in evaluating and restricting PFAS releases. Bills being considered by the Florida Legislature include:

• SB1692/HB1665: Preventing Contaminants of Emerging Concern from Discharging Into Wastewater Facilities and Waters of the State

• SB 1546/HB1533: Statewide Drinking Water Standards

The State of Louisiana has been actively addressing per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in response to the lack of comprehensive federal regulation. Here are some key points regarding PFAS regulations in Louisiana:

1. Drinking Water:

The state has set a Health Advisory Level (HAL) for PFAS in drinking water:

• 0.004 parts per trillion (ppt) for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)

• 0.02 ppt for perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)

• 10 ppt for hexafluoropropylene oxide (HFPO) dimer acid and its ammonium salt (referred to as ‘GenX chemicals’)

• 2,000 ppt for perfluorobutane sulfonic acid and its related compound potassium perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS)

Note that these HALs are not enforceable and were in place prior to the Final PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) in April 2024.

On April 12, 2024, the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality’s (LDEQ) Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) issued an open call for applications for eligible projects including, but not limited to, the construction, alteration or repair of publicly owned treatment works (POTW) as well as implementation of nonpoint source pollution control and estuary management programs. Nonpoint pollution such as storm water runoff from highways and fields can be addressed under the program as well.

https://www.deq.louisiana.gov/assets/docs/News_Releases/2022/EPA_PFAS_June2022.pdf

https://deq.louisiana.gov/assets/docs/News_Releases/2024/SRFrelease.final.4.12.pdf

2. National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES):

The State of Louisiana will follow the U.S. EPA issued memo detailing how it will address PFAS discharges in EPA-issued NPDES permits and recommended PFAS-related permit language.

3. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) and Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA):

The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) has several options for evaluating releases at sites depending on the nature of the release. The LDEQ’s Risk Evaluation/Corrective Action Program (RECAP) regulation was promulgated and became final October 2003. This regulation establishes the Department’s minimum remediation standards for present and past uncontrolled constituent releases. PFAS are not addressed in the soil and groundwater Screening or Management Options tables. However, under the Brownfields program, the LDEQ would default to the EPA Regional Screening Levels (RSLs). The RSLs are not cleanup standards and should not be used as cleanup levels. The RSL tables provide comparison values for residential and commercial/industrial exposures to soil, air, and tap water (drinking water). The unified use of the RSLs, to screen chemicals at contaminated sites, promotes national consistency.

https://deq.louisiana.gov/page/recap

https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls

https://deq.louisiana.gov/page/brownfields

The State of Louisiana does not have state required testing for PFAS compounds in drinking water. The state is waiting for the adoption of the EPA National Primary Drinking Water Regulations establishing maximum contaminant levels for 6 PFAS compounds.

Louisiana has four Federal facilities where AFFF was used. Previous investigation shows concentrations greater than 1,000,000 ppt of PFAS in groundwater around those facilities. The state has four facilities reporting detections of PFAS compounds in their drinking water greater than the current EPA MCL, and another 17 municipalities where drinking water concentrations were below EPA MCLs or the compounds do not currently have MCLs.

Interactive Map: PFAS Contamination Crisis: New Data Show 5,021 Sites in 50 States (ewg.org)

The State of Oklahoma does not have state required testing for PFAS compounds in Drinking Water. The state was waiting for the adoption of the EPA National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) establishing maximum contaminant levels for 6 PFAS compounds. The Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has protocols for PFAS sampling in drinking water, air, groundwater, surface water, fish, soil and sediments. As with most states, the DEQ relies on EPA Regional Screening Levels (RSLs) to investigate and characterize potential remediation sites.

https://www.deq.ok.gov/land-protection-division/quality-assurance/

Oklahoma has nine Federal facilities where AFFF was used. Previous investigation shows concentrations greater than 1,000 ppt of PFAS in groundwater around those facilities. The state has eight cities reporting PFAS concentration greater than the EPA MCL for NPDWR, and has 20 cities reporting detections of PFAS compounds in their drinking water but with detections below the MCL.

Interactive Map: PFAS Contamination Crisis: New Data Show 5,021 Sites in 50 States (ewg.org)

In Texas, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) oversees regulations related to evironmental media, including per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Here are the key points regarding PFAS regulations in Texas:

1. Protective Concentration Levels (PCLs):

○ The Tier 1 PCLs serve as the default cleanup standards in the Texas Risk Reduction Program (TRRP).

○ As of May 2023, the most recent update to the Tier 1 PCLs for soil and groundwater are in effect.1

○ 16 PFAS constituents have PCLs.

2. Surface Water Benchmarks:

○ The TCEQ developed Surface Water and Sediment Benchmarks for Ecological Risk Assessments for PFOS and PFOA.

https://www.tceq.texas.gov/remediation/eco

3. Drinking Water:

○ The TCEQ will develop drinking water standards and reporting requirements for public water systems (30 Texas Administrative Code [TAC] Chapter 290) now that the EPA has published the final rule.

Texas has 17 Federal facilities where AFFF was used and/or previous investigations indicate detectable concentrations of PFAS in environmental media. The state has numerous industrial facilities that used or are suspected of using PFAS and several municipalities with PFAS identified above detection and/or the MCLs in drinking water systems

Remember that regulations are evolving over time, so it’s essential to stay informed about any updates or changes. Halff maintains our website information regularly but with the quickly changing regulations, it is recommended you contact us for the most up-to-date information.

Provided there is adequate support and funding, drinking water utilities will be able to implement the new PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Standard requirements as control technologies exist and are in use today. Water treatment technologies that exist and are capable of removing PFAS from drinking water including granular activated carbon, reverse osmosis and ion exchange systems. EPA’s final rule does not dictate how water systems remove these contaminants. The rule is flexible, allowing systems to determine the best solutions for their community.

There is unprecedented funding for drinking water systems impacted by PFAS and other emerging contaminants to provide safe water to communities. We know that PFAS pollution can have a disproportionate impact on small, disadvantaged, and rural communities, and there is federal funding available specifically for these water systems. EPA announced nearly $1 billion for states and territories through the Emerging Contaminants in Small or Disadvantaged Communities (EC-SDC) grant program, which can be used to help with initial testing and treatment at public water systems, and help owners of private wells address PFAS contamination. The nearly $1 billion is part of the dedicated $9 billion of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) funding for communities with drinking water impacted by PFAS and other emerging contaminants.

An additional $12 billion in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding is available to communities to make general drinking water improvements, including addressing PFAS pollution. This funding is available through EPA programs that are part of the Justice40 Initiative, which set the goal that 40 percent of the overall benefits of certain federal investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized by underinvestment and overburdened by pollution. The BIL provides a total of $5 billion in fiscal years 2022-2026 for the Emerging Contaminants in Small or Disadvantaged Communities (EC-SDC) grant program, which focuses exclusively on addressing emerging contaminants, including perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, perchlorate, manganese and more in drinking water served by public water systems in small or disadvantaged communities. The EC-SDC grant program provides states and territories with grants rather than loans to address emerging contaminants in small or disadvantaged communities. Grants will be awarded non-competitively to states and territories.

The fiscal year 2024 funding does not have a cost share or match requirement. This grant funding, in addition to the Clean Water State Revolving Fund and the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund resources, will support states, territories and local communities in detecting, treating and mitigating the emerging contaminants (ECs) in water and facilitating state efforts to build the pipeline of projects to address them.

EPA’s free Water Technical Assistance (WaterTA) program is ensuring that disadvantaged communities can access federal funding. Too many communities across America face challenges providing safe drinking water services to their residents, and WaterTA supports communities to identify water challenges; develop plans; build technical, managerial and financial capacity; and develop application materials to access water infrastructure funding. EPA collaborates with state, tribes, territories, community partners and other key stakeholders to implement WaterTA efforts. The end result is more communities with applications for federal funding, quality water infrastructure and reliable water services.

Allotments of FY 2024 BIL – PDF

Emerging Contaminants (EC) in Small or Disadvantaged Communities Grant (SDC) – epa.gov

Fact Sheet: PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation – epa.gov

Visit website: www.grants.gov

Halff has a team of grant writing and funding resource specialists that can support your needs in evaluating funding options that best suit your community. We assess funding options as well as assist in application submittals, public meetings, and treatment option evaluations that meet the needs of your water system.

Several PFAS funding strategy outlines have been developed by Halff to evaluate the different funding options available to our clients and to help guide towards the best option for their community. An example of a funding strategy outline, specifically for Texas, was previously developed by Halff and is provided below:

| Agency: | Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) | |

| Program: | Clean Water State Revolving Fund – Emerging Contaminants Program (CWSRF-EC) | |

| Application Deadline: | April 1, 2024 | |

| Funding Type: | Loan | |

| Details: See below

Eligible Project Activities – Planning / Acquisition / Design / Construction |

||

| Wastewater treatment facilities:

(Installation of treatment technologies) |

Stormwater: (Projects to trap and/or treat contaminants in runoff) | |

| Water reuse: (Potable and non-potable water reuse / reclamation projects that apply technology to remove PFAS or other emerging contaminants) | Nonpoint source projects: (Landfills, surface water protection and restoration) | |

| Planning and design for capital projects:

• Broader water quality planning is eligible as long as the planning results in a capital project |

||

| Eligible Entities for this Program | ||

| Wastewater treatment agencies:

• Interstate agencies • Water supply corporations designated or approved as a management agency in the Texas Water Quality Management Plan |

Political subdivisions:

Cities, commissions, counties, districts, river authorities, or other public bodies with authority to dispose of sewage, industrial waste, or other waste |

|

| Intermunicipal, interstate, or State agencies | Tribal organizations | |

| Private entities for nonpoint source projects or estuary projects only | ||

| Financials | ||

| FFY 2024 CWSRF-EC Budget Availability:

• $9,719,000 |

No Required Local Match | |

| 100% Principal Forgiveness Available | ||

| Competitive Point Elements | ||

| • Must complete a Project Information Form to be included in the Initial Project Priority List (IPPL) | ||

| • Must have emerging contaminants in system | ||

| • Water Conservation and Drought Contingency Plan required if receiving assistance

> $500K |

||

| • Must be able to demonstrate an increase in systematic water loss | ||

| • Davis-Bacon Wage Rates | ||

| • American Iron & Steel | ||

| • NEPA type environmental review | ||

| • For equivalency projects only:

o Disadvantaged Business Enterprise program o Additional steps when procuring architecture and engineering services o EPA requires Build America, Buy America requirements |

||